My original plan for the month of August was to spend every waking moment doing the following:

- Making lesson plans and other classroom preparations

- Learning Swahili from a book

Instead of that, in the past couple of weeks, here is what I have been doing:

I went to a final profession of vows for 4 Capuchin Friars (Capuchins are a type of Franciscan). That sounds interesting, but what happened the night before was more interesting. I stayed up until the early hours of the morning polishing off a bottle of whiskey with two Capuchin brothers in their dorm room, discussing the legendary yet mysterious land of America and the land of the Luo tribe of Kenya (which is where Obama’s grandmother came from and these two Capuchins). For those who are worried, we weren’t intoxicated (we woke up the next morning without headaches), but we were behaving like three typical African males: enjoying life with good drinks and good friends. In fact, that seemed to be the resounding theme of our discussion on the land of the Luo—they are known throughout Kenya for seizing the day without ever thinking (i.e., worrying) about tomorrow. For example, you can tell who is a Luo at a bar, because instead of ordering one beer at a time, he will order 8 beers and proudly display them at his table. Or, from personal experience, a Luo might also stay up until early in the morning drinking whiskey with friends, even though he will take his final vows to be a Capuchin Friar the next day at 10 in the morning.

Here is a picture of one of the Luo brothers who is named Charles or, more commonly, “Obama”:

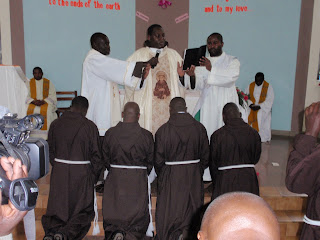

Here is a picture of the 4 Capuchin Friars professing their vows the next day:

The ceremony lasted for about 4 hours (although it started over an hour late), and the church was so packed that there were almost 50 people who had to stand outside. After the ceremony, the celebration continued with feasting and dancing until midnight.

The day before, Fr. Chris celebrated a wedding mass in the same church. This was another 3-4 hour ceremony, although the singing, dancing, and laughter was so enthralling that the mass only seemed to last for an hour. It is refreshing to see people truly celebrating their faith. At the end of the ceremony, Fr. Chris decided to call the male grandparents from both sides of the families to come up to dance together as a sign of unity. Below is a video of it (wait until the end of it so that you can hear the level of engagement and excitement of the congregation (sorry it is difficult to hear the music…)):

The next week, two college students, both of which work at St. Bridget's Friary where I live, asked me to attend a funeral in the remote area where they grew up. The ceremony was at the home of one of the college students. Her home is nestled atop a hill where you get a panorama of inexplicably beautiful rolling hills filled earthen houses, which are surrounded by farms of coffee, mango, maize, beans, and banana. Here are some pictures of one of the local ladies on her farm:

The funeral happened in typical Kenyan style: with singing, dancing, mounds of simple foods from the local farms, and spirited speeches (although all of this was a bit more somber than a usual Kenyan religious celebration).

Before the funeral, I had the pleasure of eating my lunch with the elders inside of the house. The meal was Githeri, which is a mix of white maize, beans, and a few chopped veggies. Here is a picture of the Githeri (notice that this is what the entire meal consists of):

While eating, I saw the picture below on the wall. Analyze this photograph for a second:

If one does the calculations correctly, 2006 minus 1885 is 121 years. Hmmm? I thought this was absurd. I inquired about the photo, and I discovered that this man was the builder and owner of the home I was in, and he happened to be the ancestor of what seemed to be everybody at the event. Already, this man has 365 descendents from just him and his one wife. Then, I said it is not possible that this man lived to be 121 years. Benedict, one of the college students that I came with and who is a descendent of this man, retorted that he was a farmer who grew enormously strong and healthy with his constant labor. He spent his life producing coffee and other equatorial crops, along with walking hundreds of kilometers to Mombasa with his crops carried by donkeys and cattle in order to sell his produce. The man never even saw a doctor; but, when sick, would simply go to his “shamba” (meaning “bush” or “farm”) and find a few herbs to take as tea. His diet was composed mainly of fruits, vegetables, and grain, but rarely did he eat meat. He lived as a servant to his family, with simplicity and faithfulness and without a drop of alcohol, yet he was constantly jovial. For these reasons, he lived to be 121 years.

It doesn’t matter whether or not you believe he actually lived to be 121 years, but what does matter is this man lived an incredible joyful, fruitful, prolonged life, and the reason why he lived so long is because he lived so simply and humbly—remaining content with just his basic needs being met and with constantly serving his family with strenuous manual labor. If I have discovered one thing in Kenya, it is this: it does not take much to be happy—in fact, too much will make you unhappy. It sounds like Stephen, who I think should be taken as a hero and a model, completely understood this.

Here is one last story. Last Thursday morning, I left Nairobi for a small rural town known as Kithimani in order to attend an ordination. I was told by Fr. Christopher that we would be returning the following day. By now, I have learned enough to know that we would NOT be returning the following day.

We arrived on Thursday immediately after the ceremony, which is something Fr. Chris actually planned and which meant we were there only for the feasting and the dancing. That’s exactly what we did. Here is a picture of me dancing/posing with the kids:

Here is a video of Fr. Daniel, the newly ordained priest, and the rest of the congregation dancing:

That night, we decided to stay until Saturday for Fr. Daniel’s first mass, which would take place at his parents' home. This left Friday to be used as we pleased, so we traveled to Masinga dam, which consists of a massive hydroelectric facility used to help power Nairobi. Here is a picture of us at the lake (Fr. Daniel is the one on the phone... I am the one in typical American attire...):

The mass on Saturday was an all day affair. Fr. Daniel, Fr. Chris, and myself drove to the house where the mass would be held. Two hundred meters outside of the house, we were met by an energetic crowd who took Fr. Daniel out of the car and danced and sung around him in a procession all the way to the vicinity of the house, which is where the place had been set up for mass. Here is a picture of the procession:

After lunch, Fr. Chris decided he would sneak out of the event, so that the people would not demand that he stay until the next day in order to continue the celebrations and discussions.

Fr. Chris and I left the event with his sister’s son and daughter. Therefore, we had to take them home. Once we arrived at the house, his sister and her husband, Patrick, were there. They told Fr. Chris that I should stay with them tonight, so I could experience a night with a rural farming family, and then I could go back to St. Bridget by public transportation. I thought this would be nice, but I hadn’t begun lesson planning yet, so I tried to come up with an excuse. I utterly failed… and good thing, too! I ended up staying Saturday, Sunday, and Monday, because they kept on adamantly urging me to stay, and I couldn't resist.

For those three days, I went without electricity, without running water, and with 100% pure Kenyan, organically and locally farmed, delicious home cooked food. They even slaughtered one of the chickens running freely outside for me, so that it could be cooked immediately for my lunch!

Patrick, the father of the family, is a teacher; but, as typical of most Kenyan educators, is only paid 20,000 shillings a month, which is a mere $250. This means that Patrick must also farm on his 8-acre shamba in order to provide for the simple life of his family. Here are a few facts about this Catholic family: they live in a house built by their own hands with bricks made out of the dirt from around their house, they still use bulls to pull their plough, they drink fresh milk from a couple of dairy cows, they eat fresh eggs from their several chickens, they eat meat only about once a week, a large percentage of their grains and vegetables come from their shamba, they have never owned an automobile, they have an outhouse, they bathe with a bucket and a sponge, and they are incredibly close due to the fact that they cook and eat every meal together, clean the house together, farm together, play “football” together, and sit around their lantern at night and talk and pray together.

Imagine spending three days with such a family! How could one pass up such an opportunity?

Along with participating in all of the daily activities that I discussed above, I had the opportunity to visit the school where Patrick teaches at (and where his son and daughters go to school), to attend mass at the local church, and to travel around the local area to visit some friends.

Here is a slideshow of the visit. Note that it starts with the mass on Sunday, then goes to the visit to my friend's house who was back home from her studies to become a nun in Germany, and ends with photos of Patrick's house and family:

The surge of traveling and experiencing Kenyan life is coming to a close, as I am gearing up to start teaching at Pumwani Secondary School next to one of the slums in Nairobi. I suppose now it is time to start planning for teaching; or, better yet, should I even plan at all?